This short account of the May 1942 Battle of the Coral Sea focuses on the strategically significant outcomes of the battle and how they related to the future of World War 2 and Australians in particular. ...

Colonial navies

Book Review: Australia’s Colonial Navies

Australia’s Colonial Navies by Ross Gillett is a revised and expanded edition published by the Naval Historical Society of Australia and released in 2021. In the 21st century most Australians ...

Occasional Paper 28: Cockatoo Island – An Historical Account

June 2018 Cockatoo Island has a long association with the RAN. The Island has World Heritage Listing and some additional information can be found on our website at https://navyhistory.au/naval-heritage-sites/cockatoo-island. This ...

Admirable Ancestors

The Naval Defence of the Australian Colonies to Federation

The question with regard to naval defence is ‘what were the differences with the Mother Country’ and, if there were any, what impact did they have on the federation of the six colonies? ...

Cerberus – First of the modern battleships

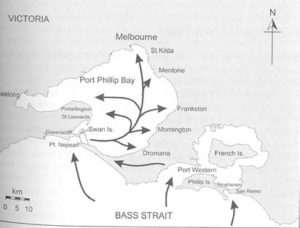

PRIOR TO FEDERATION, VICTORIA’S DEFENCES were exposed as the British naval presence was located in far away Sydney. As a result a powerful 16 ship fleet evolved. This Victorian Navy ...