You must be a logged-in member to view this post. If you recently purchased a membership it can take up to 5 days to be activated, as our volunteers only work on Tuesdays and Thursdays. If you are not a member yet or your membership just expired you can Join Now by purchasing a new membership from the shop. ...

Naval Engagements, Operations and Capabilities

The Big Guns of Tarawa

By Walter Burroughs The December 2022 edition of this magazine contained an article A Lonely and Dangerous Vigil regarding New Zealand Coastwatching operations in the Gilbert and Ellice Islands. Comments ...

Book Review: Flying Stations II

Flying Stations II. The Royal Australian Navy’s Fleet Air Arm 1998-2022. This fine book edited by Lieutenant Commander Desmond Woods OAM RAN is published by the RAN Fleet Air Arm ...

Occasional Paper 149: Nor West Capture

You must be a logged-in member to view this post. If you recently purchased a membership it can take up to 5 days to be activated, as our volunteers only work on Tuesdays and Thursdays. If you are not a member yet or your membership just expired you can Join Now by purchasing a new membership from the shop. ...

Book Review: The Scrap Iron Flotilla – Five valiant destroyers and the Australian war in the Mediterranean.

By Mike Carlton, published by Random House Australia. A 448-page illustrated paperback with photographs. Available at all good booksellers from about $30.00. Some chroniclers are ideal authors for their subject ...

Book Review: On Contested Shores

On Contested Shores. The Evolving Role of Amphibious Operations in the History of Warfare. This large paperback of 452 pages edited by Timothy Heck and B. A. Friedman was published ...

Occasional Paper 133: Operation C – The Indian Ocean showdown between British and Japanese naval might, 4 – 9 April 1942.

By Angus Britts Wednesday 8 April 1942 was a day of ignominy for the greatest naval power the modern world had thus far known. Since 30 March the Royal Navy’s ...

The Battle of Cape Spada – 19 July 1940 Part 1: The Genesis of Italy’s Light Cruiser Force

By Andreas Biermann Introduction This article is the first of two that aim to provide a new perspective on the Battle of Cape Spada on 19 July 1940, one of ...

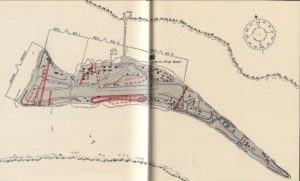

Occasional Paper 77: HMAS Assault. WWII Combined Operations Directorate Establishment – Port Stephens NSW

By Dennis J Weatherall JP TM AFAITT(L) LSM – Volunteer Researcher HMAS Assault, also known as the Amphibious Training Centre to American personnel, was a combined operations establishment for training ...

Occasional Paper 75: The Vietnam War and the Royal Australian Navy

The following address was delivered by Captain Ralph T. Derbidge MBE RAN (Retired) at the Melbourne Shrine of Remembrance to mark Vietnam Veterans Day on 18 August 2010. It describes ...