You must be a logged-in member to view this post. If you recently purchased a membership it can take up to 5 days to be activated, as our volunteers only work on Tuesdays and Thursdays. If you are not a member yet or your membership just expired you can Join Now by purchasing a new membership from the shop. ...

History - general

Occasional Paper 177: Australia’s First Tennis Match

You must be a logged-in member to view this post. If you recently purchased a membership it can take up to 5 days to be activated, as our volunteers only work on Tuesdays and Thursdays. If you are not a member yet or your membership just expired you can Join Now by purchasing a new membership from the shop. ...

Book Review: “Safe to Dive – Submarine Support in Sydney 1914 to 1999”

“Safe to Dive – Submarine Support in Sydney 1914 to 1999” by John Jeremy was published by The Naval Historical Society of Australia in 2023, under licence agreement with the ...

Occasional Paper 162: Port Phillip’s Fleet Review 1920

You must be a logged-in member to view this post. If you recently purchased a membership it can take up to 5 days to be activated, as our volunteers only work on Tuesdays and Thursdays. If you are not a member yet or your membership just expired you can Join Now by purchasing a new membership from the shop. ...

Book Review: The Far Land: 200 Years of Murder, Mania and Mutiny in the South Pacific.

The Far Land: 200 Years of Murder, Mania and Mutiny in the South Pacific. This 327-page paperback edition written by Brandon Presser was published by Icon Books of London in ...

The Newport Medieval Ship Project

This article originally appeared in the Magazine of the Institute of Conservation (ICON News) Issue 101, August 2022 and is reproduced, with minor amendments, by kind permission of the author ...

Royal Australian Navy: Fleet Reviews over the Years

By Dr J.K. Haken A Fleet Review is a British tradition where the monarch inspects the massed ships of the navy. It originally occurred when the fleet was mobilised for ...

The bizarre story of HMAS STALWART and 300 tons of rotten onions

In 1939 Sydney had a shortage of onions. A period of drought had affected the Victorian crop, and in order to fulfil the demand for the 20, 000 tonnes of ...

Letter: Ben Boyd National Park

An email was received from a member relating to the story contained in the September 2022 issue of this magazine What’s in a Name: The Ben Boyd National Park. This ...

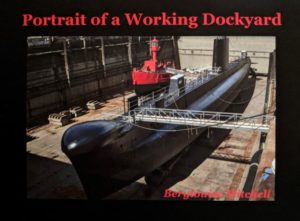

Book Review: Portrait of a Working Dockyard

Portrait of a Working Dockyard. This photobook by Berylouise Mitchell comes in a limited edition, handmade in A4 landscape format by Australia’s premier photobook printer MomentoPro in Sydney and sells ...