You must be a logged-in member to view this post. If you recently purchased a membership it can take up to 5 days to be activated, as our volunteers only work on Tuesdays and Thursdays. If you are not a member yet or your membership just expired you can Join Now by purchasing a new membership from the shop. ...

History - pre-Federation

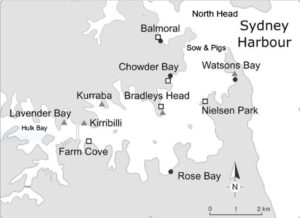

The Sydney Harbour Invasion

By Colin Randall Many Australian harbours are defended against enemy attack and none more so than Sydney, which has had shore-based fortifications since the days of the First Fleet. Potential ...

The Enterprising Enderbys

By Walter Burroughs The English Civil War During the 18th and 19th centuries the name Enderby was well-known in shipping circles in Great Britain and its colonies in America and ...

Hulks and Honey

Introduction The name Hulk Bay does not conjure up romantic notions of a sparkling Sydney Harbour; perhaps this was why it was later renamed Lavender Bay, which remains to this ...

Our First Patrol Boats

By Walter Burroughs In recent times Australia could be considered a mecca for the patrol boat industry: from a slow post war start with the Attack class, they were replaced ...

What’s in a Name: The Ben Boyd National Park

By Walter Burroughs The French Revolution of 1789 declared ‘All men are born and remain free and equal in rights’. This virtually brought about the end of slavery but it ...

Occasional Paper 140 : The Factors that Led to the Formation of the RAN in 1911

This short account of the May 1942 Battle of the Coral Sea focuses on the strategically significant outcomes of the battle and how they related to the future of World War 2 and Australians in particular. ...

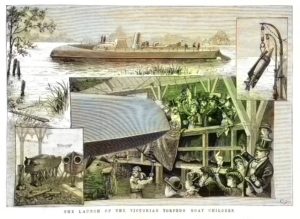

Occasional Paper 134: A Long Salty Voyage Home – The Delivery of Victoria’s First Torpedo Boat H.M.V.S. Childers

By Ross Gillett When the Victorian Government’s first-class torpedo boat HMVS Childers had moved safely out of Portsmouth on 3 February 1884, the 26-year-old commander, Lieutenant Martyn Jerram, went down ...

HMS Diamond and Desertions on the Australia Station

By John Smith The Royal Navy’s Australia Station was in existence from 1859 until 1913 when the newly created Royal Australian Navy took over the naval defence of Australia. The ...

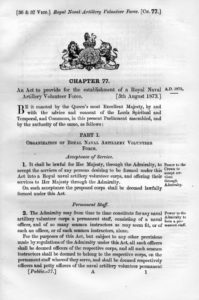

A Context for the Fremantle Naval Volunteers

By John McGrath Introduction The fascinating article by Ron and Ian Forsyth about the Fremantle Naval Volunteers1 opens the way to consideration of the way in which this force fitted ...