By Lieutenant Commander Desmond Woods RAN This paper was first published by the Australian Naval Institute online and in an abbreviated form the by the UK Naval Review and by ...

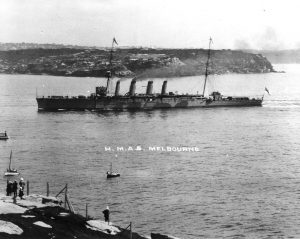

HMAS Melbourne I

HMAS Melbourne in WWI – a Diarist’s Perspective

By Kingsley Perry George Henry Iles was born at Norwood, Surrey on 11 December 1883 and later joined the Royal Navy where he became a cook. On 14 October 1912 ...

HMAS Encounter (1905 – 1932)

HMS Encounter served on the Australia Station and was later commissioned into the RAN. She played a vital role in defence of the eastern coast of Australia, and the anti raider patrols in the South West Pacific. She was regarded as “more beloved than any other unit of our fleet”. ...

Book Review: The Forgotten Cruiser HMAS Melbourne 1913-1928

The Forgotten Cruiser HMAS Melbourne 1913-1928 By Andrew Kilsby and Greg Swinden, Longueville Media, Woollahra, NSW, 2013. Available from cooeehistory.com RRP $49.95. On 26 March 1913, HMAS Melbourne, Australia’s first ...

The Career of Vice Admiral Mortimer L’Estrange Silver, CBE, RN.

HMAS Adelaide 1918 – 1949

90 Years on: Rabaul and Sydney/Emden 1914

This article was originally published in ‘Semaphore’, the newsletter of the Sea Power Centre – Australia. It is republished with the kind agreement of the Sea Power Centre. This year ...