The Scrap Iron Flotilla by Mike Carlton. William Heinemann Australia. Paperback of 448 pages. rrp $34.99 On Sunday September 3rd 1939, history was tumbling over itself. In the mess decks ...

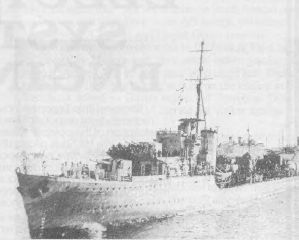

HMAS Napier

Book Review: The Kellys

The Kellys – British J, K & N Class Destroyers of World War II By Christopher Langtree Published by Chatham Publishing, Kent, England Distributed in Australia by Peribo 58 Beaumont Street, ...

Obituary: Ian Hunter McDonald RAN (1915-1996)

On 25 November 1996, 55 years to the day of the sinking of HMS Barham, in which he was serving and when 862 of his shipmates lost their lives, Captain ...

The RAN’s Destroyers

Spakhia

ON A SMALL BAY on the south coast of Crete is a village or township called Spakhia. Landward approaches are steep-to and the harbour has – or had – no ...

Captain A.S. Rosenthal DSO and Bar, OBE, RAN

With the Ns in Japanese Waters

Nestor died slowly

Australian Naval History on 17 January 1956

HMS NAPIER, (destroyer), formerly HMAS NAPIER, was paid off for disposal. ...

Australian Naval History on 28 November 1945

HMAS QUALITY was commissioned into the RAN after service in the RN. She replaced HMAS NAPIER on transfer to the RAN. ...