By Lorraine Fildes The Burma Campaign was a series of battles fought in the British colony of Burma. The campaign was waged against the Japanese in Burma, eastern India and ...

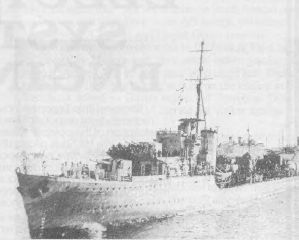

HMAS Norman I

HMAS Norman – far from Home

By Peter Nunan Background The N-class destroyers operated in many parts of the globe but HMAS Norman was the only one of her ilk to have made an operational voyage to ...

Book Review: The Kellys

The Kellys – British J, K & N Class Destroyers of World War II By Christopher Langtree Published by Chatham Publishing, Kent, England Distributed in Australia by Peribo 58 Beaumont Street, ...

The RAN’s Destroyers

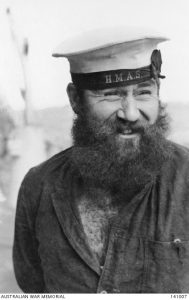

Captain A.S. Rosenthal DSO and Bar, OBE, RAN

Australian Naval History on 1 April 1958

HMS NORMAN, (destroyer), formerly HMAS NORMAN, was paid off for disposal. ...

Australian Naval History on 28 October 1945

HMAS Norman decommissioned and was transferred back to the Royal Navy and was broken up in 1958 ...

Australian Naval History on 20 October 1945

HMAS QUEENSBOROUGH was commissioned into the RAN after service in the RN. She replaced HMAS NORMAN on transfer to the RAN. ...

Australian Naval History on 20 May 1945

HMAS NORMAN,(destroyer), took under tow HMS QUILLIAM, (destroyer), which was damaged in a collision with HMS INDOMITABLE, (aircraft carrier). HMAS KIAMA, (minesweeper), bombarded Japanese troop positions and installations on the ...

Australian Naval History on 16 May 1945

HM Ships INDOMITABLE, (aircraft carrier), and QUILLIAM, (destroyer), collided off Okinawa. HMAS NORMAN, (destroyer), stood by to assist the damaged QUILLIAM. ...