You must be a logged-in member to view this post. If you recently purchased a membership it can take up to 5 days to be activated, as our volunteers only work on Tuesdays and Thursdays. If you are not a member yet or your membership just expired you can Join Now by purchasing a new membership from the shop. ...

HMAS Voyager II

Letter: HMAS Melbourne Repairs

The following letter has been received from John Jeremy who for many years served at Cockatoo Island Dockyard being its last Chief Executive. Dear Walter, The March 2022 edition of ...

Occasional Paper 129: Service on the Fleet Commander’s Staff, 1964: A Personal Reflection

By John Ingram The following personal reflection by Commander John Ingram OAM RAN RTD describes his experience and observations of the fateful collision between HMA Ships Melbourne and Voyager on ...

The Albert Medal

By John Ellis Queen Victoria instituted the Albert Medal in 1866 to recognise those civilians who had attempted to prevent the loss of life at sea. A year later the ...

The HMAS Melbourne-Voyager Collision: A Tragedy that Damaged and Reformed

By MIDN Mollie Burns, RAN – NEOC 54 Naval Historical Society Prizewinning Essay Introduction The collision of HMAS Melbourne and HMAS Voyager remains the Royal Australian Navy’s (RAN) worst peacetime disaster. Occurring ...

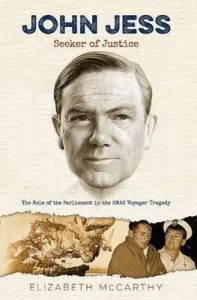

Book Review: John Jess, Seeker of Justice

By Elizabeth McCarthy. Sid Harta Publishers, Melbourne, 2015. Paperback 320 pages. RRP $29.95 but discounts available. This book, published in August 2015, was written by a daughter of John Jess ...

The Melbourne/Voyager Collision – Untold Story

The RAN’s Destroyers

Australian Naval History on 10 February 1991

Sunday, 10 February 1991 marked the 27th anniversary of the loss of HMAS Voyager (II). A large contingent of survivors embarked in Swan at Port Kembla to take passage to ...